User Interfaces: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (41 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

As part of our short course on [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/astrowiki/index.php/Python_for_Physics_and_Astronomy Python for Physics and Astronomy] we consider how users interact with their computing environment. A programming language such as Python provides tools to build code that computes scientific models, captures data, sorts it and analyzes it largely without operator action. In effect, once you have written the program, you point it at the data or task it is to do, and wait for it to return new science to you. This is the command line, or batch, model of computing and is at the core of large data science today. Indeed, from your handheld devices to supercomputers, the work that is done is for the most part autonomous. We have seen how Python has built-in components to accept input from the command line, the operating system, the computer that is hosting the program, and the Internet or cloud. What about the other side, the user's perspective on computing? | |||

As | As an end user, would you prefer to move a mouse or tap a screen in order to select a file, or to type in the path and file name? What if you had to make operational decisions based on graphical output, or changing real world environments as data are collected? In modern computing, most of us interact with the machine and software through a graphical user interface or GUI. These tools create that option. | ||

'''On-Line Guides''' | |||

*[http://www.tkdocs.com/ Tk] | |||

*[https://matplotlib.org/users/index.html Matplotlib] | |||

*[https://bokeh.pydata.org/en/latest/docs/reference.html#refguide Bokeh] | |||

While the conventional Tk and Matplotlib components are foundational to Python, Bokeh is a very recent development with the design philosophy to put the web first for the end user and it has a contemporary look. It also enables adding widgets written for javascript within the web display, which can be be very effective. | |||

== Command Line Interfacing and Access to the Operating System == | === Command Line Interfacing and Access to the Operating System === | ||

In a | In a Unix-like enviroment (Linux or MacOSX), the command line is an accessible and often preferred way to instruct a program on what to do. A typical program, as we've seen, might start like this example to interpolate a data file and plot the result: | ||

#!/usr/bin/python | #!/usr/bin/python | ||

| Line 138: | Line 146: | ||

#!/usr/bin/python | #!/usr/bin/python | ||

# Process images in a directory | # Process images in a directory tree | ||

import os | import os | ||

| Line 151: | Line 159: | ||

sys.exit("Usage: process_fits.py directory\n") | sys.exit("Usage: process_fits.py directory\n") | ||

toplevel = sys.argv[ | toplevel = sys.argv[1] | ||

# Search for files with this extension | # Search for files with this extension | ||

| Line 182: | Line 190: | ||

=== Graphical User Interface to Plotting === | |||

First, read the [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/astrowiki/index.php/Graphical_User_Interface_with_Python comprehensive section on Tkinter] to see how that code works, and then the one on [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/astrowiki/index.php/Graphics_with_Python graphics with Python] to learn the basics of the plotting toolkits. In this section we combine Tk for control with interactive graphics. Our goals are to | |||

* Retain the features of the graphics display with its interactivity and style | |||

* Use tkinter to offer the user access to new features such loading files and processing data | |||

* Allow real-time updating so that the plot can follow changing data | |||

To this end we will write a Python 3 program that uses tkinter and add matplotlib or bokeh to make useful tools that also serve as templates of your own development. The two resulting programs are almost identical except for the plotting functions, and you will find them on the [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/classes/650/python/examples/ examples page]. Look for "tk_plot.py" and "bokeh_plot.py". | |||

Before we begin, check that bokeh and tkinter are available in your version of Python 3. The version of Tk should be at least 8.6, which you can check with | |||

tkinter.TkVersion | |||

on the command line after importing tkinter. For bokeh, use | |||

bokeh.__version__ | |||

that's with two underscores before and after the "version". Look for version 0.12.15 or greater to have the functionality described here. | |||

'''The Tk Framework''' | |||

We begin our code as usual by requiring these libraries | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

from tkinter import ttk | |||

from tkinter import filedialog | |||

from tkinter import messagebox | |||

such that Tk functions require the "tk." and ttk functions use "ttk". We have also included file dialog and message widgets that were mentioned in the summary of Tk widgets. | |||

For connection to the operating system we need "os" and "sys", and for handling data we use numpy | |||

import os | |||

import sys | import sys | ||

from | import numpy as np | ||

def | There are global variables that are used to pass information from file handlers and processing to the graphics components | ||

global selected_files | |||

global x_data | |||

global y_data | |||

selected_files = [] | |||

x_data = np.zeros(1024) | |||

y_data = np.zeros(1024) | |||

x_axis_label = "" | |||

y_axis_label = "" | |||

We will create a Tk window with button or other widgets that require call backs when they are activated. Since these programs are templates for what can be done, look at the examples to see how the call backs are structured. The one to read a data file illustrates how to use Python to parse a file and save its data in numpy arrays. | |||

def read_file(infile): | |||

global x_data | |||

global y_data | |||

datafp = open(infile, 'r') | |||

datatext = datafp.readlines() | |||

datafp.close() | |||

# How many lines were there? | |||

i = 0 | |||

for line in datatext: | |||

i = i + 1 | |||

nlines = i | |||

# Fill the arrays for fixed size is much faster than appending on the fly | |||

x_data = np.zeros((nlines)) | |||

y_data = np.zeros((nlines)) | |||

# Parse the lines into the data | |||

i = 0 | |||

for line in datatext: | |||

# Test for a comment line | |||

if (line[0] == "#"): | |||

pass | |||

# Treat the case of a plain text comma separated entries | |||

try: | |||

entry = line.strip().split(",") | |||

x_data[i] = float(entry[0]) | |||

y_data[i] = float(entry[1]) | |||

i = i + 1 | |||

except: | |||

# Treat the case of space separated entries | |||

try: | |||

entry = line.strip().split() | |||

x_data[i] = float(entry[0]) | |||

y_data[i] = float(entry[1]) | |||

i = i + 1 | |||

except: | |||

pass | |||

return() | |||

Notice how we allow for both comma separated and space delimited data. The expectation is that the file will have two values per line, the first one being "x" and the second one being "y". They may have white space between them, or be separated by a comma. Files written this way are very common, and easy to use too, but we may not know before reading one which style it was written in. Also common (in Grace, for example), a "#" at the beginning of a line indicates a comment and implies to ignore the entire line. The reader simply skips lines that begin with "#". A more advanced reader would validate the numbers as they come in to prevent errors later. This one simply assigns them to two global arrays, one for x and one for y, because that is the format required for plotting 2D data by both matplotlib and bokeh. Also, having the data in numpy offers the options of other processing based on the GUI. | |||

The file that is being read has been selected with a Tk widget that returns filenames in a global list | |||

def select_file(): | |||

global selected_files | |||

# Use the tk file dialog to identify file(s) | |||

newfile = "" | |||

try: | |||

newfile, = tk.filedialog.askopenfilenames() | |||

selected_files.append(newfile) | |||

except: | |||

tk_info.set("No file selected") | |||

if newfile !="": | |||

tk_info.set("Latest file: "+newfile) | |||

return() | |||

By holding onto all the selections in s list, we retain the option of going back to them later. However here in the file selection call back, we take only the first file that the user selects to add to that list. Of course we take all of them and process the one by one. The Tk function will return leaving the selected_files list with its new entry as the last one on the list, and display its name on the user interface. | |||

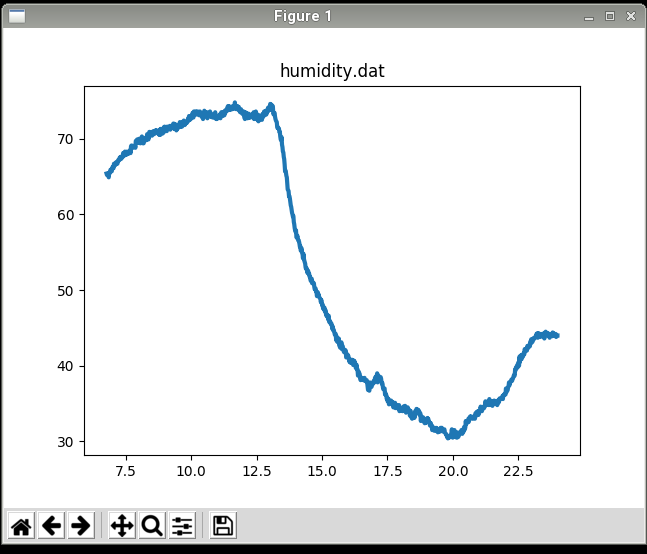

'''Matplotlib from Tk on the Desktop''' | |||

For matplotlib we need | |||

import matplotlib as mpl | |||

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt | |||

mpl.use('TkAgg') | |||

The Plot button call back uses matplotlib with its pyplot namespace to create a plot on the matplotlib canvas. The plot is not embedded in the Tk user interface in order to invoke the matplotlib toolbar, which in version 2.2 is deprecated for Tk. This solution avoids that issue, but also means that it is not possible to update the content of the displayed data through the Tk interface. | |||

# Create the desired plot | |||

def make_plot(event=None): | |||

global selected_files | |||

global x_axis_label | |||

global y_axis_label | |||

nfiles = len(selected_files) | |||

this_file = selected_files[nfiles-1] | |||

read_file(this_file) | |||

# Create the plot using bokeh | |||

this_file_basename = os.path.basename(this_file) | |||

base, ext = os.path.splitext(this_file_basename) | |||

bokeh_file = base+".html" | |||

output_file(bokeh_file) | |||

p = figure(tools="hover,crosshair,pan,wheel_zoom,box_zoom,box_select,reset") | |||

p.line(x_data, y_data, line_width=2) | |||

show(p) | |||

# Create the desired plot with matplotlib | |||

def make_plot(event=None): | |||

global selected_files | |||

global x_axis_label | |||

global y_axis_label | |||

nfiles = len(selected_files) | |||

this_file = selected_files[nfiles-1] | |||

read_file(this_file) | |||

# Create the plot. | |||

plt.figure(nfiles) | |||

plt.plot(x_data, y_data, lw=3) | |||

plt.title(this_file) | |||

plt.xlabel(x_axis_label) | |||

plt.ylabel(y_axis_label) | |||

plt.show() | |||

Input is handled through global variables, and the axis labels may be assigned through the Tk interface, though in tk_plot.py that is left for the next version. | |||

[[File:Humidity_tk.png]] | |||

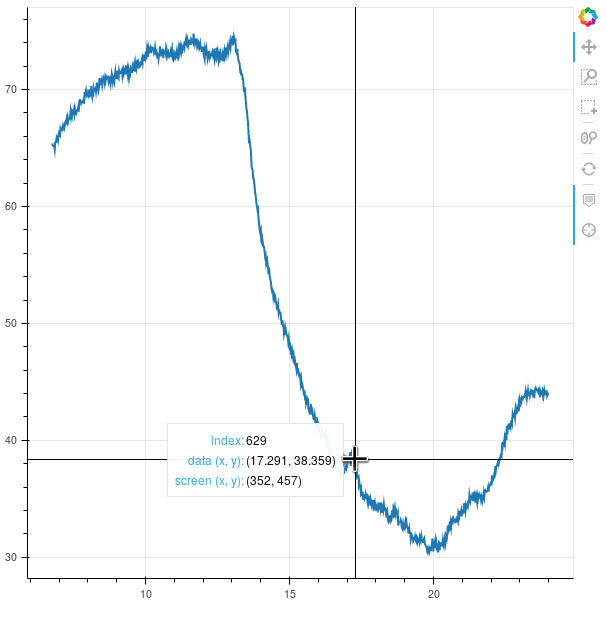

'''Bokeh from Tk in the Browser and on the Web''' | |||

We include the bokeh modules needed for a basic plot | |||

from bokeh.plotting import figure, output_file, show | |||

For bokeh the call back is very similar | |||

# Create the desired plot with bokeh | |||

def make_plot(event=None): | |||

global selected_files | |||

global x_axis_label | |||

global y_axis_label | |||

nfiles = len(selected_files) | |||

this_file = selected_files[nfiles-1] | |||

read_file(this_file) | |||

# Create the plot using bokeh | |||

this_file_basename = os.path.basename(this_file) | |||

base, ext = os.path.splitext(this_file_basename) | |||

bokeh_file = base+".html" | |||

output_file(bokeh_file) | |||

p = figure(tools="hover,crosshair,pan,wheel_zoom,box_zoom,box_select,reset") | |||

p.line(x_data, y_data, line_width=2) | |||

show(p) | |||

The tools are explicitly requested, unlike matplotlib which provides a tool bar that is fully populated. | |||

[[File:Humidity_bokeh.png]] | |||

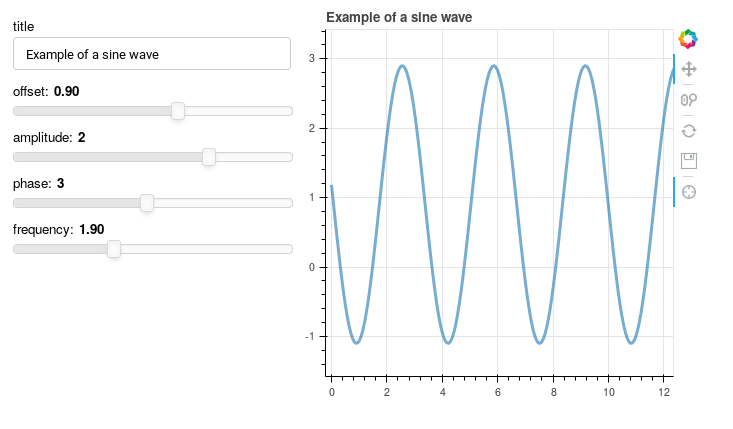

=== Running a Bokeh Server for Live Plotting of Python Data === | |||

Lastly, we arrive at the destination: a solution to interactive plotting where data are created and modified in Python, and presented to the user on the fly, with a customized and responsive interface. The interface components can be entirely in the browser, and thereby potentially offered to a web client, or they can be shared between the browser and a Python GUI, for desktop applications. There are three components: | |||

* Python backend, perhaps with Tk or other GUI or responding to CGi requests from another server | |||

* Bokeh server responding to the Python and presenting information to the browser | |||

* Browser client, listening to the Bokeh server directly or through a proxy, and providing data to the Python backend if needed | |||

For details on how to set this up and its possible uses, see | |||

[https://bokeh.pydata.org/en/latest/docs/user_guide/server.html Running a Bokeh Server] | |||

Several examples are offered here | |||

[https://demo.bokehplots.com/ demo.bokehplots.com] | |||

The first live example shown there is from "sliders.py", a copy of which is in our [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/classes/650/python/examples examples directory]. | |||

# Load the modules | |||

import numpy as np | |||

from bokeh.io import curdoc | |||

from bokeh.layouts import row, widgetbox | |||

from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource | |||

from bokeh.models.widgets import Slider, TextInput | |||

from bokeh.plotting import figure | |||

# Set up data using numpy | |||

N = 200 | |||

x = np.linspace(0, 4*np.pi, N) | |||

y = np.sin(x) | |||

# Set up the display data source | |||

source = ColumnDataSource(data=dict(x=x, y=y)) | |||

# Set up plot | |||

plot = figure(plot_height=400, plot_width=400, title="my sine wave", | |||

tools="crosshair,pan,reset,save,wheel_zoom", | |||

x_range=[0, 4*np.pi], y_range=[-2.5, 2.5]) | |||

plot.line('x', 'y', source=source, line_width=3, line_alpha=0.6) | |||

# Set up widgets similar to Tk | |||

text = TextInput(title="title", value='my sine wave') | |||

offset = Slider(title="offset", value=0.0, start=-5.0, end=5.0, step=0.1) | |||

amplitude = Slider(title="amplitude", value=1.0, start=-5.0, end=5.0, step=0.1) | |||

phase = Slider(title="phase", value=0.0, start=0.0, end=2*np.pi) | |||

# Add interactive tools | |||

freq = Slider(title="frequency", value=1.0, start=0.1, end=5.1, step=0.1) | |||

# Set up callbacks to the widgets | |||

def update_title(attrname, old, new): | |||

plot.title.text = text.value | |||

text.on_change('value', update_title) | |||

def update_data(attrname, old, new): | |||

# Get the current slider values | |||

a = amplitude.value | |||

b = offset.value | |||

w = phase.value | |||

k = freq.value | |||

# Generate the new curve | |||

x = np.linspace(0, 4*np.pi, N) | |||

y = a*np.sin(k*x + w) + b | |||

source.data = dict(x=x, y=y) | |||

for w in [offset, amplitude, phase, freq]: | |||

w.on_change('value', update_data) | |||

# Set up layouts and add to document | |||

inputs = widgetbox(text, offset, amplitude, phase, freq) | |||

curdoc().add_root(row(inputs, plot, width=800)) | |||

curdoc().title = "Sliders" | |||

Download the file sliders.py or copy the source shown, and on a computer that has Python 3 and Bokeh installed, use the command line | |||

bokeh server sliders.py | |||

to initiate a live session in the server. Once that has started, open your browser to "localhost", that is to your own computer, by entering this on the browser source line | |||

http://localhost:5006/sliders | |||

The display will look like this, except the sliders will cause changes in the plot. | |||

[[File:Sliders.png]] | |||

=== Running a Server for Javascript in a Browser Engine === | |||

Python includes packages that enable a simple webserver which may be used to run advanced graphics operations through javascript within a browser's javascript engine. We will cover use of javascript, and Three.js in particular, as a supplement or replacement for 3D visualization in Python. In order to do this without the burden of managing a full Apache installation, we turn to Python. This shell script in Linux will start a web server in the directory that the script is running in: | |||

python -m CGIHTTPServer 8000 1>/dev/null 2>/dev/null & | |||

echo "Use localhost:8000" | |||

echo | |||

By using port 8000 the server is distinct from the one on port 80 used for web applications. The site would appear by putting | |||

http://localhost:8000 | |||

in a Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox browser window running on the same user account on the same machine. Note the redirects for stdio and stderr to /dev/null keeps output from appearing in the console. The server may be killed by identifying its process ID in Linux with the command | |||

ps -e | grep python | |||

followed by | |||

kill -s 9 pid | |||

where "pid" is the ID number found in the first line. Alternatively, if it is the only python process running you may kill it with | |||

killall python | |||

Any file in the directory tree below the starting directory is now accessible in the browser, and html files will be parsed to run the included javascript. If here is a cgi-bin directory at the top level, the server will see it and use it. One use of this low level server is to create a virtual instrument that is accessible from the web, but not exposed to it directly. A remote web server on the same network that can access port 8000 on the instrument machine can run code and get response from the instrument by calling cgi-bin operations. | |||

For programmers, however, this utility allows development and debugging of web software without the need for a large server. | |||

Latest revision as of 07:02, 17 April 2018

As part of our short course on Python for Physics and Astronomy we consider how users interact with their computing environment. A programming language such as Python provides tools to build code that computes scientific models, captures data, sorts it and analyzes it largely without operator action. In effect, once you have written the program, you point it at the data or task it is to do, and wait for it to return new science to you. This is the command line, or batch, model of computing and is at the core of large data science today. Indeed, from your handheld devices to supercomputers, the work that is done is for the most part autonomous. We have seen how Python has built-in components to accept input from the command line, the operating system, the computer that is hosting the program, and the Internet or cloud. What about the other side, the user's perspective on computing?

As an end user, would you prefer to move a mouse or tap a screen in order to select a file, or to type in the path and file name? What if you had to make operational decisions based on graphical output, or changing real world environments as data are collected? In modern computing, most of us interact with the machine and software through a graphical user interface or GUI. These tools create that option.

On-Line Guides

While the conventional Tk and Matplotlib components are foundational to Python, Bokeh is a very recent development with the design philosophy to put the web first for the end user and it has a contemporary look. It also enables adding widgets written for javascript within the web display, which can be be very effective.

Command Line Interfacing and Access to the Operating System

In a Unix-like enviroment (Linux or MacOSX), the command line is an accessible and often preferred way to instruct a program on what to do. A typical program, as we've seen, might start like this example to interpolate a data file and plot the result:

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys import numpy as np from scipy.interpolate import UnivariateSpline import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

sfactorflag = True

if len(sys.argv) == 1:

print " "

print "Usage: interpolate_data.py indata.dat outdata.dat nout [sfactor]"

print " "

sys.exit("Interpolate data with a univariate spline\n")

elif len(sys.argv) == 4:

infile = sys.argv[1]

outfile = sys.argv[2]

nout = int(sys.argv[3])

sfactorflag = False

elif len(sys.argv) == 5:

infile = sys.argv[1]

outfile = sys.argv[2]

nout = int(sys.argv[3])

sfactor = float(sys.argv[4])

else:

print " "

print "Usage: interpolate_data.py indata.dat outdata.dat nout [sfactor]"

print " "

sys.exit("Interpolate data with a univariate spline\n")

It uses "sys" to parse the command line arguments into text and numbers that control what the program will do. Because its first line directs the system to use the python interpreter, if the program is marked as executable to the user it will run as a single command followed by arguments. In this case it would be something like

interpolate_data.py indata.dat outdata.dat nout sfactor

where indata.dat is a text-based data file of x,y pairs, one pair per line, outdata.dat is the interpolated file, nout is the number of points to be interpolated, and sfactor is an optional floating point smoothing factor. When you run this it will read the files, do the interpolation without further interaction, and (as written) plot a result as well as write out a data file. The rest of the code is

# Take x,y coordinates from a plain text file

# Open the file with data

infp = open(infile, 'r')

# Read all the lines into a list

intext = infp.readlines()

# Split data text and parse into x,y values

# Create empty lists

xdata = []

ydata = []

i = 0

for line in intext:

try:

# Treat the case of a plain text comma separated entry

entry = line.strip().split(",")

# Get the x,y values for these fields

xval = float(entry[0])

yval = float(entry[1])

xdata.append(xval)

ydata.append(yval)

i = i + 1

except:

try:

# Treat the case of a plane text blank space separated entry

entry = line.strip().split()

xval = float(entry[0])

yval = float(entry[1])

xdata.append(xval)

ydata.append(yval)

i = i + 1

except:

pass

# How many points found?

nin = i

if nin < 1:

sys.exit('No objects found in %s' % (infile,))

# Import data into a np arrays x = np.array(xdata) y = np.array(ydata)

# Function to interpolate the data with a univariate cubic spline if sfactorflag: f_interpolated = UnivariateSpline(x, y, k=3, s=sfactor) else: f_interpolated = UnivariateSpline(x, y, k=3)

# Values of x for sampling inside the boundaries of the original data x_interpolated = np.linspace(x.min(),x.max(), nout) # New values of y for these sample points y_interpolated = f_interpolated(x_interpolated)

# Create an plot with labeled axes

plt.figure().canvas.set_window_title(infile)

plt.xlabel('X')

plt.ylabel('Y')

plt.title('Interpolation')

plt.plot(x, y, color='red', linestyle='None', marker='.', markersize=10., label='Data')

plt.plot(x_interpolated, y_interpolated, color='blue', linestyle='-', marker='None', label='Interpolated', linewidth=1.5)

plt.legend()

plt.minorticks_on()

plt.show()

# Open the output file outfp = open(outfile, 'w') # Write the interpolated data for i in range(nout): outline = "%f %f\n" % (x[i],y[i]) outfp.write(outline) # Close the output file outfp.close() # Exit gracefully exit()

Aftet the fitting is done the program runs pyplot to display the results. The interactive window it opens and manages is a GUI, but it has been set up by the command line code. Of course there are many variations on command line interfacing, and the one shown here with coded argument parsing is perhaps the simplest and would serve as a template for most applications. Python offers other ways to manage the command line too. The os module is useful to have access to the operating system from within a Python routine. Some examples are

import os

os.chdir(path) changes the current working directory (CWD) to a new one os.getcdw() returns the CWD os.getenv(varname) returns the value of the environment variable varname

and there are many more, providing within the Python program many of the command line operating system tools available on the system. Here's an example of how that might be used in a program that processes many files in a directory:

#!/usr/bin/python

# Process images in a directory tree

import os import sys import fnmatch import string import subprocess import pyfits

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print " "

sys.exit("Usage: process_fits.py directory\n")

toplevel = sys.argv[1]

# Search for files with this extension pattern = '*.fits'

for dirname, dirnames, filenames in os.walk(toplevel):

for filename in fnmatch.filter(filenames, pattern):

fullfilename = os.path.join(dirname, filename)

try:

# Open a fits image file

hdulist = pyfits.open(fullfilename)

except IOError:

print 'Error opening ', fullfilename

break

# Do the work on the files here ...

# You can call a separate system process outside of Python this way

darkfile = 'dark.fits'

infilename = filename

outfilename = os.path.splitext(os.path.basename(infilename))[0]+'_d.fits'

subprocess.call(["/usr/local/bin/fits_dark.py", infilename, darkfile, outfilename])

exit()

Here we used the os module's routines to walk through a directory tree, parse filenames, and then perform another operation on those files that is a separate command line Python program. Command line tools used to leverage the operating system's built-in functions can be very powerful, and take hours out of actually running a program on a large database.

Graphical User Interface to Plotting

First, read the comprehensive section on Tkinter to see how that code works, and then the one on graphics with Python to learn the basics of the plotting toolkits. In this section we combine Tk for control with interactive graphics. Our goals are to

- Retain the features of the graphics display with its interactivity and style

- Use tkinter to offer the user access to new features such loading files and processing data

- Allow real-time updating so that the plot can follow changing data

To this end we will write a Python 3 program that uses tkinter and add matplotlib or bokeh to make useful tools that also serve as templates of your own development. The two resulting programs are almost identical except for the plotting functions, and you will find them on the examples page. Look for "tk_plot.py" and "bokeh_plot.py".

Before we begin, check that bokeh and tkinter are available in your version of Python 3. The version of Tk should be at least 8.6, which you can check with

tkinter.TkVersion

on the command line after importing tkinter. For bokeh, use

bokeh.__version__

that's with two underscores before and after the "version". Look for version 0.12.15 or greater to have the functionality described here.

The Tk Framework

We begin our code as usual by requiring these libraries

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import ttk from tkinter import filedialog from tkinter import messagebox

such that Tk functions require the "tk." and ttk functions use "ttk". We have also included file dialog and message widgets that were mentioned in the summary of Tk widgets.

For connection to the operating system we need "os" and "sys", and for handling data we use numpy

import os import sys import numpy as np

There are global variables that are used to pass information from file handlers and processing to the graphics components

global selected_files global x_data global y_data

selected_files = [] x_data = np.zeros(1024) y_data = np.zeros(1024) x_axis_label = "" y_axis_label = ""

We will create a Tk window with button or other widgets that require call backs when they are activated. Since these programs are templates for what can be done, look at the examples to see how the call backs are structured. The one to read a data file illustrates how to use Python to parse a file and save its data in numpy arrays.

def read_file(infile): global x_data global y_data

datafp = open(infile, 'r') datatext = datafp.readlines() datafp.close()

# How many lines were there?

i = 0

for line in datatext:

i = i + 1

nlines = i

# Fill the arrays for fixed size is much faster than appending on the fly

x_data = np.zeros((nlines)) y_data = np.zeros((nlines))

# Parse the lines into the data

i = 0

for line in datatext:

# Test for a comment line

if (line[0] == "#"):

pass

# Treat the case of a plain text comma separated entries

try:

entry = line.strip().split(",")

x_data[i] = float(entry[0])

y_data[i] = float(entry[1])

i = i + 1

except:

# Treat the case of space separated entries

try:

entry = line.strip().split()

x_data[i] = float(entry[0])

y_data[i] = float(entry[1])

i = i + 1

except:

pass

return()

Notice how we allow for both comma separated and space delimited data. The expectation is that the file will have two values per line, the first one being "x" and the second one being "y". They may have white space between them, or be separated by a comma. Files written this way are very common, and easy to use too, but we may not know before reading one which style it was written in. Also common (in Grace, for example), a "#" at the beginning of a line indicates a comment and implies to ignore the entire line. The reader simply skips lines that begin with "#". A more advanced reader would validate the numbers as they come in to prevent errors later. This one simply assigns them to two global arrays, one for x and one for y, because that is the format required for plotting 2D data by both matplotlib and bokeh. Also, having the data in numpy offers the options of other processing based on the GUI.

The file that is being read has been selected with a Tk widget that returns filenames in a global list

def select_file():

global selected_files

# Use the tk file dialog to identify file(s)

newfile = ""

try:

newfile, = tk.filedialog.askopenfilenames()

selected_files.append(newfile)

except:

tk_info.set("No file selected")

if newfile !="":

tk_info.set("Latest file: "+newfile)

return()

By holding onto all the selections in s list, we retain the option of going back to them later. However here in the file selection call back, we take only the first file that the user selects to add to that list. Of course we take all of them and process the one by one. The Tk function will return leaving the selected_files list with its new entry as the last one on the list, and display its name on the user interface.

Matplotlib from Tk on the Desktop

For matplotlib we need

import matplotlib as mpl import matplotlib.pyplot as plt mpl.use('TkAgg')

The Plot button call back uses matplotlib with its pyplot namespace to create a plot on the matplotlib canvas. The plot is not embedded in the Tk user interface in order to invoke the matplotlib toolbar, which in version 2.2 is deprecated for Tk. This solution avoids that issue, but also means that it is not possible to update the content of the displayed data through the Tk interface.

# Create the desired plot

def make_plot(event=None): global selected_files global x_axis_label global y_axis_label nfiles = len(selected_files) this_file = selected_files[nfiles-1] read_file(this_file)

# Create the plot using bokeh this_file_basename = os.path.basename(this_file) base, ext = os.path.splitext(this_file_basename) bokeh_file = base+".html" output_file(bokeh_file) p = figure(tools="hover,crosshair,pan,wheel_zoom,box_zoom,box_select,reset") p.line(x_data, y_data, line_width=2) show(p) # Create the desired plot with matplotlib

def make_plot(event=None): global selected_files global x_axis_label global y_axis_label nfiles = len(selected_files) this_file = selected_files[nfiles-1] read_file(this_file)

# Create the plot. plt.figure(nfiles) plt.plot(x_data, y_data, lw=3) plt.title(this_file) plt.xlabel(x_axis_label) plt.ylabel(y_axis_label) plt.show()

Input is handled through global variables, and the axis labels may be assigned through the Tk interface, though in tk_plot.py that is left for the next version.

Bokeh from Tk in the Browser and on the Web

We include the bokeh modules needed for a basic plot

from bokeh.plotting import figure, output_file, show

For bokeh the call back is very similar

# Create the desired plot with bokeh

def make_plot(event=None): global selected_files global x_axis_label global y_axis_label nfiles = len(selected_files) this_file = selected_files[nfiles-1] read_file(this_file)

# Create the plot using bokeh this_file_basename = os.path.basename(this_file) base, ext = os.path.splitext(this_file_basename) bokeh_file = base+".html" output_file(bokeh_file) p = figure(tools="hover,crosshair,pan,wheel_zoom,box_zoom,box_select,reset") p.line(x_data, y_data, line_width=2) show(p)

The tools are explicitly requested, unlike matplotlib which provides a tool bar that is fully populated.

Running a Bokeh Server for Live Plotting of Python Data

Lastly, we arrive at the destination: a solution to interactive plotting where data are created and modified in Python, and presented to the user on the fly, with a customized and responsive interface. The interface components can be entirely in the browser, and thereby potentially offered to a web client, or they can be shared between the browser and a Python GUI, for desktop applications. There are three components:

- Python backend, perhaps with Tk or other GUI or responding to CGi requests from another server

- Bokeh server responding to the Python and presenting information to the browser

- Browser client, listening to the Bokeh server directly or through a proxy, and providing data to the Python backend if needed

For details on how to set this up and its possible uses, see

Several examples are offered here

The first live example shown there is from "sliders.py", a copy of which is in our examples directory.

# Load the modules

import numpy as np

from bokeh.io import curdoc from bokeh.layouts import row, widgetbox from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource from bokeh.models.widgets import Slider, TextInput from bokeh.plotting import figure

# Set up data using numpy

N = 200 x = np.linspace(0, 4*np.pi, N) y = np.sin(x)

# Set up the display data source

source = ColumnDataSource(data=dict(x=x, y=y))

# Set up plot

plot = figure(plot_height=400, plot_width=400, title="my sine wave", tools="crosshair,pan,reset,save,wheel_zoom", x_range=[0, 4*np.pi], y_range=[-2.5, 2.5])

plot.line('x', 'y', source=source, line_width=3, line_alpha=0.6)

# Set up widgets similar to Tk

text = TextInput(title="title", value='my sine wave') offset = Slider(title="offset", value=0.0, start=-5.0, end=5.0, step=0.1) amplitude = Slider(title="amplitude", value=1.0, start=-5.0, end=5.0, step=0.1) phase = Slider(title="phase", value=0.0, start=0.0, end=2*np.pi)

# Add interactive tools

freq = Slider(title="frequency", value=1.0, start=0.1, end=5.1, step=0.1)

# Set up callbacks to the widgets

def update_title(attrname, old, new):

plot.title.text = text.value

text.on_change('value', update_title)

def update_data(attrname, old, new):

# Get the current slider values

a = amplitude.value

b = offset.value

w = phase.value

k = freq.value

# Generate the new curve

x = np.linspace(0, 4*np.pi, N)

y = a*np.sin(k*x + w) + b

source.data = dict(x=x, y=y)

for w in [offset, amplitude, phase, freq]:

w.on_change('value', update_data)

# Set up layouts and add to document inputs = widgetbox(text, offset, amplitude, phase, freq)

curdoc().add_root(row(inputs, plot, width=800)) curdoc().title = "Sliders"

Download the file sliders.py or copy the source shown, and on a computer that has Python 3 and Bokeh installed, use the command line

bokeh server sliders.py

to initiate a live session in the server. Once that has started, open your browser to "localhost", that is to your own computer, by entering this on the browser source line

http://localhost:5006/sliders

The display will look like this, except the sliders will cause changes in the plot.

Running a Server for Javascript in a Browser Engine

Python includes packages that enable a simple webserver which may be used to run advanced graphics operations through javascript within a browser's javascript engine. We will cover use of javascript, and Three.js in particular, as a supplement or replacement for 3D visualization in Python. In order to do this without the burden of managing a full Apache installation, we turn to Python. This shell script in Linux will start a web server in the directory that the script is running in:

python -m CGIHTTPServer 8000 1>/dev/null 2>/dev/null & echo "Use localhost:8000" echo

By using port 8000 the server is distinct from the one on port 80 used for web applications. The site would appear by putting

http://localhost:8000

in a Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox browser window running on the same user account on the same machine. Note the redirects for stdio and stderr to /dev/null keeps output from appearing in the console. The server may be killed by identifying its process ID in Linux with the command

ps -e | grep python

followed by

kill -s 9 pid

where "pid" is the ID number found in the first line. Alternatively, if it is the only python process running you may kill it with

killall python

Any file in the directory tree below the starting directory is now accessible in the browser, and html files will be parsed to run the included javascript. If here is a cgi-bin directory at the top level, the server will see it and use it. One use of this low level server is to create a virtual instrument that is accessible from the web, but not exposed to it directly. A remote web server on the same network that can access port 8000 on the instrument machine can run code and get response from the instrument by calling cgi-bin operations.

For programmers, however, this utility allows development and debugging of web software without the need for a large server.