Graphical User Interface with Python: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (51 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Python is inherently a programming language ideal for data analysis, and it works well by simply entering commands and seeing the results immediately. | |||

Python is inherently a programming language ideal for data analysis, and it works well by simply entering commands and seeing the results immediately, as we have seen in our short course on [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/astrowiki/index.php/Python_for_Physics_and_Astronomy Python for Physics and Astronomy].For longer programs, or ones that are used frequently, the code is usually written into a file and then executed from the command line or as an element of a more complex set of scripted operations. However many users prefer a graphical user interface or "GUI" where mouse clicks, drop-down menus, check boxes, images, and plots access with the mouse and sometimes the keyboard. Python has that too, through a selection of tools that can be added to your code. | |||

The most developed core component for this purpose is the Tk/Tcl library. In its most recent versions it provides a very direct way of running your programs within a GUI that is attractive, matches the native machine windows in appearance, and is highly responsive. While this is not the only one, it is a solid starting point and may be all you need. Later in this tutorial we will show you how to use Python running in background behind a graphical interface in a browser window which is another technique that is growing in capability as the browsers themselves gain computing power. However, the Tk library will allow you to build free-standing graphical applications that will run on all platforms on which Python runs. | The most developed core component for this purpose is the Tk/Tcl library. In its most recent versions it provides a very direct way of running your programs within a GUI that is attractive, matches the native machine windows in appearance, and is highly responsive. While this is not the only one, it is a solid starting point and may be all you need. Later in this tutorial we will show you how to use Python running in background behind a graphical interface in a browser window which is another technique that is growing in capability as the browsers themselves gain computing power. However, the Tk library will allow you to build free-standing graphical applications that will run on all platforms on which Python runs. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 23: | ||

root = Tk() | root = Tk() | ||

mainframe = ttk.Frame(root, padding=3 3 12 12") | mainframe = ttk.Frame(root, padding="3 3 12 12") | ||

and if we wanted to use a string inside the tkinter program we would have | and if we wanted to use a string inside the tkinter program we would have | ||

| Line 32: | Line 34: | ||

import tkinter as tk | import tkinter as tk | ||

from tkinter import ttk | from tkinter import ttk | ||

or this works too | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

import tkinter.ttk | |||

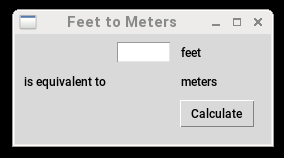

Now we have to use "tk" along with the component we are taking from tkinter, but the resulting code is much clearer. Let's complete a program that will convert feet to meters, following an example from the Tk website. | Now we have to use "tk" along with the component we are taking from tkinter, but the resulting code is much clearer. Let's complete a program that will convert feet to meters, following an example from the Tk website. | ||

| Line 83: | Line 90: | ||

* import tkinter | * import tkinter | ||

* define | * define any functions such as "calculate" that you want to run | ||

* create a graphical environment "root" | * create a graphical environment "root" window | ||

* add a frame to the | * add a frame to the window | ||

* put a grid inside the window frame | |||

* add widgets for your interface located within the grid | |||

* pad the widgets with space so they look good and Tk does the rest | |||

* start the user interface | |||

If you start the Python interpreter in a shell and perform the operations step by step up, as soon as the root object is created, a GUI window will appear on the screen. What comes after determines the properties of that display and its contents. For example, adding a title has a obvious effect to this window. | If you start the Python interpreter in a shell and perform the operations step by step up, as soon as the root object is created, a GUI window will appear on the screen. What comes after determines the properties of that display and its contents. For example, adding a title has a obvious effect to this window. | ||

The window contains a frame which is called "mainframe" here, and when that is added the window shrinks to fit the frame. It is quite small because the frame does not contain anything but a few pixels of padding around its border. You can, at this point grab the edges of the tiny box and stretch it on your screen. The command | The window contains a frame which is called "mainframe" here, and when that is added the window shrinks to fit the frame. It is quite small because the frame does not contain anything but a few pixels of padding around its border. You can, at this point grab the edges of the tiny box and stretch it on your screen. The command | ||

mainframe.grid(column=0, row=0, sticky=(tk.N, tk.W, tk.E, tk.S)) | |||

creates a grid that is anchored to tk points N, W, E, and S, that is to the corners. Within the grid we add components that will make our interface, and each component has properties we can set too. In this program we will have a frame that will enclose the our interface, and the window will resize automatically to enclose everything. The Tk grid handles the location of the "widgets" that are the elements your interface, and at least for many applications will make creating an nice-looking GUI simple. | |||

First, we add the frame: | |||

mainframe.columnconfigure(0, weight=1) | |||

mainframe.rowconfigure(0, weight=1) | |||

Then we define the strings that will hold input and the output from the box that will accept the input: | |||

feet = tk.StringVar() | |||

feet_entry = tk.ttk.Entry(mainframe, width=7, textvariable=feet) | |||

The object called "feet_entry" represents this box on the screen. The box is located inside the GUI by the grid that is defined in mainframe | |||

feet_entry.grid(column=2, row=1, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E)) | |||

and we put it in column 2 and row 1. As soon as this is issued, a box appears in the GUI and is centered because there is nothing more there. The result of the calculation will be a string that we will show on the interface as a label below the input in the second row | |||

meters = tk.StringVar() | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, textvariable=meters).grid(column=2, row=2, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E)) | |||

Notice how the string is given as a variable without quotes, so the interface will update when this variable changes. Along with this, we include fixed labels for the input units, an explanation and the output units: | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="feet").grid(column=3, row=1, sticky=tk.W) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="is equivalent to").grid(column=1, row=2, sticky=tk.E) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="meters").grid(column=3, row=2, sticky=tk.W) | |||

Lastly, we add a button that will start the calculation | |||

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Calculate", command=calculate).grid(column=3, row=3, sticky=tk.W) | |||

All of these elements are children of the frame, and to have them appear on the grid with a little padding we take each one and configure the grid for it | |||

for child in mainframe.winfo_children(): | |||

child.grid_configure(padx=5, pady=5) | |||

Now focus the window on the entry box to make it easy on the user and use the Return key to start a conversion (as well as the button) | |||

feet_entry.focus() | |||

root.bind('<Return>', calculate) | |||

The GUI is ready to use. Start it with this | |||

root.mainloop() | |||

You will find this program among our [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/classes/650/python/examples/ examples] as the file "feet_to_meters_tk_explicit.example". | |||

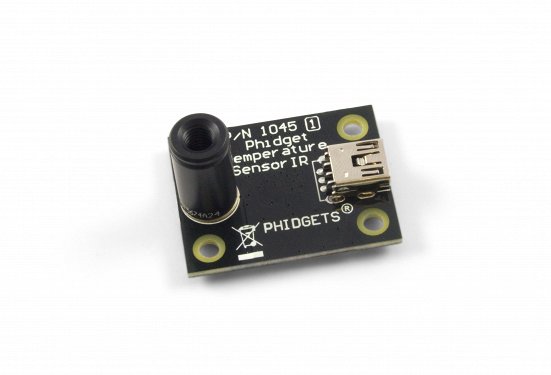

== Interfacing an Instrument: Phidgets == | |||

The power of a graphical user interface or GUI is that it is easy to use when the actions are repetitive and the end user does not need to know the details of what is happening. It will deliver to the user the result that is needed and even provide cues on how to make that happen. As in the calculation of a feet to meters conversion, the GUI does not inform the user of how it is done, and simply does it without a fuss. In a laboratory environment that can be very useful, assuming the user understands the process, and needs the answer on a single click. An example would be if there is an instrument which is capable of making a measurement and the user needs to know the result. | |||

The Canadian Company [https://www.phidgets.com/ Phidgets] manufactures a wide variety of small modules for the hobbiest, lab, and even industry that provide control of motors, relays digital signal levels, analog to digital (ADC) and digital to analog (DAC) conversion, and environmental sensors for temperature, humidty, pressure, light level, and stress. Their hardware has been traditionally designed to interface with computers using the USB bus, and recently (2017) they introduced a simpler 2-wire interface that is more versatile for some applications. They also make single board computers to run their devices under Linux. Their products are not unlike the famous [https://www.raspberrypi.org/ Rasberry Pi] or [https://beagleboard.org/ Beagle Board] systems, except they are uniformly supported, consistently manufactured, and offered with supporting opensource software. Conceptually it offers an Internet of Things for the lab. Of course there are many other vendors with similar intent, [https://nidaqmx-python.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ National Instruments] with their proprietary and mostly Windows-only LabVIEW software, [https://labjack.com/ Labjack] with cost effective versatile interfaces and solid cross-platform Python support, and [https://www.mccdaq.com/ Measurement Computing] with cutting edge interfaces supported in Linux and Python worthy of consideration. Whatever you pick for your lab experiments, if it has a Python library or module, you will have access to the device from within the Python program. Therefore, it may be useful to have an example of what can be done to interface a user with a device through a Tk GUI. | |||

The instrument we will use is an [https://www.phidgets.com/?tier=3&catid=14&pcid=12&prodid=1041 infrared thermometer] from Phidgets because it uses interesting basic physics, and it is so easily interfaced the device technology does not intrude on showing the programming elements. The device is very small, and is powered from the USB interface. It consists of an infrared sensing pyrometer that is internally a Peltier array of thermocouples, and the electronics to connect it to the computer through the standard bus. The black anodized aluminum cylinder is baffled such that infrared light from a spot 10 degrees in diameter (1 meter at a distance of 11.4 meters) illuminates the sensor. The electronics make a measurement of the IR radiation by determining the voltage from the Peltier array, which is to say the temperature it reaches in equilibrium with the incident radiation. It also measures the ambient temperature. The signal it gets is fundamentally the blackbody temperature of the 10 degree spot, and the device functions as a non-contact thermometer that can measure from -70 to +380 celsius with a temperature resolution of 0.02 C and an error of 4 C. | |||

[[File:1045_1B.jpg]] | |||

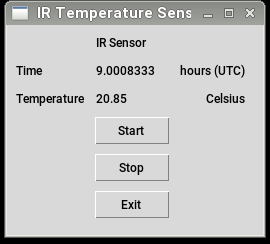

The program which uses this device is similar to the one for doing a conversion calculation, but it takes its data from the instrument instead, beginning this way -- | |||

#!/usr/bin/python3 | |||

# Phidgets IR temperature sensor example program | |||

# Driven by IR sensor change | |||

# Added utc logging | |||

import sys | |||

import time | |||

from time import gmtime, strftime # for utc | |||

from time import sleep # for delays | |||

from Phidget22.Devices.TemperatureSensor import * | |||

from Phidget22.PhidgetException import * | |||

from Phidget22.Phidget import * | |||

from Phidget22.Net import * | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

from tkinter import ttk | |||

# | |||

# Initial parameters | |||

# | |||

global site_longitude | |||

global diagnostics | |||

global time_utc | |||

global temperature_celsius | |||

global polling_flag | |||

You'll notice there are modules loaded from the Phidget22 package that the company supplies. These modules have an application programming interface (an "API") that we can use to control are get information from the sensor. The other new items are declarations that some variables are global, meaning that they will be used in other subroutines. The full program is on the examples page [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/classes/650/python/examples/ tk_temperature.example]. | |||

The graphical interface is built as before | |||

# Create the root window | |||

root = tk.Tk() | |||

root.title("IR Temperature Sensor") | |||

# Add a frame to the window | |||

mainframe = tk.ttk.Frame(root, padding="3 3 12 12") | |||

mainframe.grid(column=0, row=0, sticky=(tk.N, tk.W, tk.E, tk.S)) | mainframe.grid(column=0, row=0, sticky=(tk.N, tk.W, tk.E, tk.S)) | ||

mainframe.columnconfigure(0, weight=1) | |||

mainframe.rowconfigure(0, weight=1) | |||

# Create Tk strings for displayed information | |||

tk_temperature_celsius = tk.StringVar() | |||

tk_time_utc = tk.StringVar() | |||

tk_temperature_celsius.set('100.') | |||

tk_time_utc.set('0.') | |||

#Add widgets to the grid within the frame | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="IR Sensor").grid(column=2, row=1, sticky=tk.W) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="Time").grid(column=1, row=2, sticky=tk.W) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, textvariable=tk_time_utc).grid(column=2, row=2, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E)) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="hours (UTC)").grid(column=3, row=2, sticky=tk.W) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="Temperature").grid(column=1, row=3, sticky=tk.W) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, textvariable=tk_temperature_celsius).grid(column=2, row=3, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E)) | |||

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="Celsius").grid(column=3, row=3, sticky=tk.E) | |||

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Start", command=start_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=4, sticky=tk.W) | |||

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Stop", command=stop_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=5, sticky=tk.W) | |||

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Exit", command=exit_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=6, sticky=tk.W) | |||

# Pad the widgets for appearance | |||

for child in mainframe.winfo_children(): | |||

child.grid_configure(padx=5, pady=5) | |||

The sensor is connected to the code as soon as the GUI is built with this | |||

# Open a connection to the sensor and assign a channel | |||

try: | |||

ch = TemperatureSensor() | |||

except RuntimeError as e: | |||

print("Runtime Exception %s" % e.details) | |||

print("Press Enter to Exit...\n") | |||

readin = sys.stdin.read(1) | |||

exit(1) | |||

which attempts to connect to and if that fails exits with an error message. Once connected, it tells the instrument code how to respond to events | |||

ch.setOnAttachHandler(TemperatureSensorAttached) | |||

ch.setOnDetachHandler(TemperatureSensorDetached) | |||

ch.setOnErrorHandler(ErrorEvent) | |||

ch.setOnTemperatureChangeHandler(TemperatureChangeHandler) | |||

which are self-explanatory functions that do something when the event occurs. The important one for our use is | |||

def TemperatureChangeHandler(self, temperature): | |||

global temperature_celsius | |||

global time_utc | |||

global polling_flag | |||

temperature_celsius = temperature | |||

time_utc = utcnow() | |||

if polling_flag: | |||

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f')) | |||

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f')) | |||

Here the global variables are used to communicate with the handler. They take the temperature that is identified as having changed and save it so we can use it in other places, they note the time of the measurement, and they set two tk string variables that will display the temperature and the time. The polling_flag is used as an on/off switch on the user interface. It is changed on response to a button press to start or stop the sensor readings. Alternatively we could poll the sensor ourselves, either by a button press or by a timer of some sort, but this method lets the intrument interface tell us when it has a new value. | |||

# Define the button press actions | |||

def start_irsensor(): | |||

global temperature_celsius | |||

global time_utc | |||

global polling_flag | |||

polling_flag = True | |||

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f')) | |||

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f')) | |||

return() | |||

def stop_irsensor(): | |||

global temperature_celsius | |||

global time_utc | |||

global polling_flag | |||

polling_flag = False | |||

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f')) | |||

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f')) | |||

return() | |||

def exit_irsensor(): | |||

try: | |||

ch.close() | |||

except PhidgetException as e: | |||

print("Phidget Exception %i: %s" % (e.code, e.details)) | |||

if diagnostics: | |||

print("Press Enter to Exit...\n") | |||

readin = sys.stdin.read(1) | |||

exit(1) | |||

print("Closed TemperatureSensor device") | |||

exit(0) | |||

return() | |||

We then start the GUI and let it update the temperature while giving us control to start and stop the updates, or exit the program with a button press. | |||

# | |||

# Polling loop within GUI | |||

# | |||

if diagnostics: | |||

print("Gathering data ...") | |||

# Temperature change handler will provide new data | |||

# Tk standard is to use this blocking method | |||

root.mainloop() | |||

exit() | |||

The running program looks like this: | |||

[[File:ir_sensor_gui.png]] | |||

== Events and Control Within the User Interface == | |||

When a tkinter program has created the interface the last step is to make it responsive to the user. In these examples you'll see this function call | |||

root.mainloop() | |||

without an argument. That turns over control to the tkinter system that will idle waiting for an event for which it has been told to respond. An example is a button press, as above, which was programmed with a line such as this one | |||

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Exit", command=exit_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=6, sticky=tk.W) | |||

that created a button to exit the program. When this button is depressed or clicked, the routine "exit_irsensor()" is run. In this example that routine disconnects the program from the sensor and cleanly closes up. Other buttons in our program set flags and variables that determine how the program operates. Notice that the events are all generated within tk. Our external event is a change in the value of the temperature that is measured. That change is sensed by a different process that is running asynchronously and not directly in communication with tk. We have made them work together by having the separate process -- the handler for a change in temperature value -- set the string that displays this temperature. Whenever that string is set, an event is created that tk notices, and it updates the display. | |||

Tkinter programs are designed to use the root.mainloop() function to keep the display responsive to the user. However root.mainloop() is "blocking" any other operations. If, for example, we wanted to poll the device from within our program we could not do that because the program is in an infinite loop looking for user input to the interface. There is, however, a simple solution. Instead of starting root.mainloop() and letting it run, we tell it to also run another routine after it has started. It is done this way: | |||

root.after(2000, measure_temperature) | |||

root.mainloop() | |||

The ''after'' method takes arguments that are the delay time in milliseconds and the name of the function. The mainloop starts a timer and 2000 milliseconds later it runs measure_temperature() | |||

def measure_temperature(): | |||

if polling_flag: | |||

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f')) | |||

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f')) | |||

# Reschedule event in 2 seconds | |||

root.after(2000, measure_temperature) | |||

which upates the temperature on the display if polling_flag is true. It also tells mainloop to schedule another run of measure_temperature after 2000 more milliseconds, and so on. | |||

We have simply modified the previous example where the temperature measurement is done in another process set up by the Phidgets22 library and left the values of temperature and time in global variables for us to use later. More commonly, we could have made the measure here instead by calling that method on the open channel of the device: | |||

def measure_temperature(): | |||

global temperature_celsius | |||

global time_utc | |||

global polling_flag | |||

global ch | |||

if polling_flag: | |||

temperature_celsius = ch.getTemperature() | |||

time_utc = utcnow() | |||

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f')) | |||

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f')) | |||

root.after(2000, measure_temperature) | |||

Here we see for the first time one of the bottlenecks of computing that runs a sequence of commands on a single ''thread''. Because it can only do one thing at a time, it cannot be taking data and displaying it and talking with the operator. To accomplish that you would need multiple threads or multiple processes and a way for these components to communicate with one another and stay in step, that is to synchronize with one another. One solution is to start separate processes that run asynchronously and let them communicate with a protocol you would design. This can be simple message passing through files or first-in-first-out buffers, or something more sophisticated that can manage multiple events with suitable responses. Another is to introduce threading, where the code maintains multiple synchronized paths of processing. Threading can be quite difficult to code however, and it is usually restricted to staying on one processor, so it does not take advantage of the many CPU's that are on modern hardware. | |||

We will encounter this issue again when we look at methods of incorporating responsive graphics and visualization into your programs, since those inevitably will use other modules that will take control of your program and disable the responsiveness of a tk interface. For now, we have solved it by letting the process that takes data alert tk to take another measurement later, effectively building an infinite loop within the tk.mainloop(). This version of the program is on the examples page [http://prancer.physics.louisville.edu/classes/650/python/examples/ tk_temperature_polling.example]. | |||

== Widgets Reference == | |||

The Tkinter widgets include the usual ones, and they are simple to implement. For reference, here they are with brief examples. For details that go beyond a tutorial, consult the [https://docs.python.org/3/library/tkinter.html reference for Tkinter with Python 3], but be aware that as of April 2018 the information in the documentation applied to tk version 8.5 and is not up to date. Similarly, many of the older help lists and examples have to be consulted with caution because they apply methods to "improve" the older tk. | |||

=== Add Tk === | |||

In Python 3 with tk 8.6 and higher use | |||

from tkinter import * | |||

to get the base code, and | |||

from tkinter.ttk import * | |||

to get the ttk library of addition widgets. | |||

When imported in this way, we do not require the "tk." before using its functions. Preferrably, as is good programming practice with other modules and to be clear about what is from tk use | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

import tkinter.ttk | |||

and preface all tkinter commands with tk as we do here. The ttk library must be explicity added and when done in this way its components must be identified with .ttk as well. For example, tk.Label is part of the base, but tk.ttk.ComboBox is added from the ttk library. You have seen examples of this in the tutorial above. | |||

=== Create a Window === | |||

The first thing to do when building a GUI is to create the window it will live in | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

window = tk.Tk() | |||

window.title("My Application") | |||

window.mainloop() | |||

Not that using "tk.TK()" is required if tkinter is imported as "tk". | |||

=== Set Window Size === | |||

Use the geometry function to set the window size in pixels | |||

window.geometry('640x320') | |||

=== Optionally Add a Frame === | |||

A frame widget inside a window is a container for other widgets. It is optional, and used to simplify layout, add border spacing, or distinguish regions of a window. In the first examples of Tk GUI programming we wrote | |||

root = tk.Tk() | |||

mainframe = ttk.Frame(root, padding="3 3 12 12") | |||

and then added widgets to the mainframe rather than to the root. In these examples to make it simpler we add them to the root window without including the surrounding frame, but in a complex user interface you may want to have one or more frames and within them the various widgets to do your work. | |||

=== Use mainloop() === | |||

A tk interface program is made active by invoking the default | |||

window.mainloop() | |||

as above. This enables the tk interface to service events. We have illustrated a workaround when your program needs to do something else by invoking the "after" option, but in general simply running the mainloop is the best approach combined with other processes that are coded to interact with your interface or queried on a button press. | |||

The commands may be entered into an on-line active session and the elements of the interface will appear in real time with each one, the simplest being text inserted into the window. | |||

=== Create a Label === | |||

Labels are added to a window with | |||

lbl = tk.Label(window, text="Hello World") | |||

The label is widget that will appear where it is told to in the window, and is distinct from the title. We use a grid to locate this widget and others in the working window space. | |||

=== Grid === | |||

The grid function locates the widget components within a window, starting from column 0 and row 0 at the upper left. It is a property of the widget and is set with | |||

widget_name.grid(column=x, row=y) | |||

The lbl we created would be added to the window when it is placed on the grid with | |||

lbl.grid(column=1, row=0) | |||

We will not see it until it is assigned to the grid. | |||

There is also a "pack" function which will try to locate the elements in the window for you. The two are not mutually compatible, and grid is the best option to get a nice looking result with minimum effort and maximum control. Widgets may be placed within their grid locations by adding a "sticky" value to their properties as we have seen elsewhere in this section on Tkinter. | |||

=== Set the Font for a Label === | |||

Select the style and size in points this way: | |||

lbl = tk.Label(window, text="Hello World", font=("Arial Bold", 50)) | |||

without needing other add-ons to Tkinter. Be cautious in using older methods with Tk version 8.6 and later, which has improved the styling and default selections to make a nice interface out of the box. The fonts that are available will depend on your computer's operating system. One way to tell is to run LibreOffice and see the font names offered there and try those. | |||

=== Scrolled Text for Output === | |||

It may be useful to display more than a few words and confine them to a scrolled box on the grid. For that we need to add | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

import tkinter.scrolledtext | |||

txt = tk. scrolledtext.ScrolledText(window,width=40,height=10) | |||

txt.grid(column=0,row=0) | |||

txt.insert("insert","Text to display goes here") | |||

The contents can be dynamic, and to remove it from beginning to end use | |||

txt.delete(1.0,2.0) | |||

where the first argument is line 1, character 0, and the second one is line 2 character 0. This deletes all the content within that range. You can delete a specific character by specifying one argument in the format line.character. Similarly, the insert function can be specific to a location, such ast | |||

txt.insert(1.7," My new text has been inserted at character 7 on line 1. ") | |||

=== Entry for Text Input === | |||

An Entry widget accepts user text. You may specify the width of space allocated when it is created: | |||

txt = tk.Entry(window,width=10) | |||

=== Message Boxes === | |||

If you want your program to inform its user about something, then use | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

import tkinter.messagebox | |||

response = tk.messagebox.showinfo("Title", "Content") | |||

The box pops up in its own window with the title and content you designate (notice it is not connect to an existing window) when it is executed, and it asks for a user to click "OK" to make it disappear. Usually this action will be generated by running code that needs to alert the user to a situation, or by a button press by the user asking for information. In the event of an error or warning, there are two variants that create a different appearance to the user | |||

response = tk.messagebox.showwarning("Title", "Warning Content") | |||

response = tk.messagebox.showerror("Title", "There has been an error") | |||

both requesting an "OK" response from the user. All of these message boxes return a string that is "ok". For other possible responses, tkinter has | |||

response = tk.messagebox.askquestion('Question title','Question content') which returns "yes" or "no" | |||

response = tk.messagebox.askyesno('Yes or no title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False | |||

response = tk.messagebox.askyesnocancel('Yes or nor cancel title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False or no response | |||

response = tk.messagebox.askokcancel('OK or cancel title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False | |||

response = tk.messagebox.askretrycancel('OK or retry title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False | |||

each of which has a distinctive look to the user. | |||

=== File Selection Menu === | |||

To create a file selection dialog | |||

and return an | import tkinter as tk | ||

import tkinter.filedialog | |||

selected_files = tk.filedialog.askopenfilenames() | |||

and the chosen files are return in a tuple. The entries in the tuple are strings with the ''full path'' and file name. The dialog appears in the operating system's default interface, and allows multiple selections with the usual mouse operations. | |||

There are options to select and return a directory | |||

selected_directory = tk.filedialog.askdirectory() | |||

and operating system-specific methods of setting an initial directory | |||

from os import path | |||

selected_file = tk.filedialog.askopenfilename(initialdir= path.dirname("Full path to directory goes here")) | |||

and again the selected file has the full path in its name. | |||

=== Window Menubar === | |||

The window may have a menu added across the top, as most do. To have one with a "File" on the menubar and a "New" in the dropdown that comes from clicking it, use | |||

import tkinter as tk | |||

from tkinter import Menu | |||

program_menu = tk.Menu(window) | |||

program_menu_item = tk.Menu(program_menu) | |||

program_menu_item.add_command(label='New') | |||

program_menu.add_cascade(label='File', menu=program_menu_item) | |||

window.config(menu=program_menu) | |||

If the window exists, when the configuration change is made the menu bar will appear. Other items may be added in the same way. For example the lines | |||

program_menu_item.add_command(label='New') | |||

program_menu_item.add_separator() | |||

program_menu_item.add_command(label='Edit') | |||

with a separation between the components. By default there is a tearoff feature at the top that permits the user to detach the menu. It is disabled with | |||

program_menu_item = tk.Menu(program_menu, tearoff=0) | |||

when the dropdown menu is created. Each item in the menu should have a response function added so it really does something when selected | |||

program_menu_item.add_command(label='New', command=new_item_function) | |||

where the "new_item_function" has previously been defined. | |||

=== Button === | |||

Add a button to the interface | |||

btn = tk.Button(window, text="Run") | |||

btn.grid(column=2, row=1) | |||

=== Combobox -- A Dropdown Menu === | |||

This widget ''from the ttk library'' adds the familar dropdown menu to the interface | |||

my_list = tk.ttk.Combobox(window) | |||

and you would create the selections with | |||

my_list['values']= ("1", "2","More than 2") | |||

The default selection is set with | |||

my_list.current(2) | |||

to pick the item from the tuple used to create the list | |||

=== Checked Box === | |||

A checked selection is made with | |||

tk_chk_state = tk.BooleanVar() | |||

tk_chk_state.set(True) | |||

chk = tk.ttk.Checkbutton(window, text='This Choice', var=tk_chk_state) | |||

Its value is accessed in code by the setter and getter | |||

tk_chk_state.set(True) or tk_chk_state.set(False) | |||

chk_status = tk_check_state.get() | |||

=== Radio Buttons === | |||

A set of "radio" buttons are ones that allow one and only one selection. The would usually be created with text and placed in a grid row or a column like this: | |||

rad1 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='First Choice', value='A', command=radio_selected_1) | |||

rad2 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='Second Choice', value='B', command=radio_selected_2) | |||

rad3 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='Third Choice', value='C', command=radio_selected_3) | |||

rad1.grid(column=1, row=0) | |||

rad2.grid(column=1, row=1) | |||

rad3.grid(column=1, row=2) | |||

In this example we have added a callback command radio_selected() which would be defined before creating the Radiobutton and would respond according the selection. The callback could be different for each choice. The radio buttons do not have a getter, that is, you cannot ask for rad1.get(). Instead, add a variable to the button | |||

tk_radio_selection = tk.StringVar() | |||

rad3 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='Third Choice', value='C', variable=tk_radio_selection) | |||

and then get the value of the selection with | |||

tk_radio_selection.get() | |||

=== Spinbox -- Selecting a Number === | |||

Commonly used to set a single number, a spinbox is included in the base Tkinter | |||

spin = tk.Spinbox(window, from_=0, to=100, width=5) | |||

spin.grid(column=3, row=10) | |||

The numerical values must be integers. A specfic list of values may be inserted instead | |||

spin = tk.Spinbox(window, values=(16, 32, 64, 128), width=10) | |||

and the list may also be floating point, or text rather than numbers. The default would be set according to the content of this list. If they are all strings, then | |||

tk_spin_input = tk.StringVar() | |||

tk_spin_input.set("Item 3") | |||

spin = tk.Spinbox(window, values=("Item 1", "Item 2", "Item 3", "Item 4"), width=10, textvariable=tk_spin_input) | |||

will cause the default selection to match the textvariable in the configuration of the spinbox. When the textvariable changes, the spin box will also update. | |||

=== Use Configure to Change Properties === | |||

Properties of widgets may be changed responsively withing a program by using the configure function attached to its widget. There was an example above in the handling of an event. | |||

lbl.configure(text="String to use for the label goes here") | |||

and the text may be a string variable, a formatted number, a fixed string built into the code in this example. Similarly, properties of widget such as color may be altered while the program is running. | |||

The attribute "configure" for a widget allows us to change its colors as well, for example | |||

lbl.configure(bg="cyan") | |||

will turn the default background to cyan in real time. | |||

=== Foreground and Background Colors === | |||

Add color to a button background and text with "bg" and "fg", such as | |||

btn = tk.Button(window, text="Run", bg="green", fg="red") | |||

Colors may be precisely set by giving the rgb hex code instead of a name. So for example, to get pure green you would use | |||

bg="#00ff00" | |||

which turns on the green bits and turns off the red and blue bits. Similarly blue would be "#0000ff" | |||

and red woud be "#ff0000". There are web tools for trying different mixes and finding a hex code for the color you like. Just type "color picker" in Google search and it should be the top return, interactively displayed in the browser. | |||

=== Handle Events === | |||

If a button is depressed or another event on the interface is detected, you may direct the response to a function: | |||

def my_btn_handler(): | |||

lbl.configure(text="Do not touch that button!!") | |||

or any other routine you want. Be aware that the mainloop is blocking, and the interface will be non-responsive while handling the request. It is best to run complex responses as another process and to design communications between processes that may update and set GUI interface features on their own. | |||

Add the callback to the widget when it is built: | |||

btn = tk.Button(window, text="Run", command=btn_handler) | |||

The "command" configuration of the button names the function without the parentheses. | |||

=== Focus === | |||

Focus a program on a particular widget (such as a data entry or drop down menu) with | |||

widget_name.focus() | |||

before starting the main loop, or during execution of the code. | |||

=== Disable or Enable a Widget === | |||

If you want the widget not to respond, disable it by setting the state property | |||

txt = tk.Entry(window, width=10, state='disabled') | |||

or enable a disabled state with the "enabled" property. Widgets are enabled by default. | |||

=== Adjusting Appearance with Added Spacing === | |||

A widget in a window may be padded so that it takes up more space, which with a grid would increase the overall size of the window while making the widgets less crowded. This gives you the option of small adjustments to the appearance of the user interface without sacrificing the convenience of having the code adjust the grid for you. Padding is added by specifying pixels in x and y | |||

lbl = tk.Label(window, text="This lable takes space", padx=20, pady=10) | |||

lbl.grid(column=3, row=5) | |||

== Credits and References == | |||

* [http://www.tkdocs.com/tutorial/ Tk Docs Tutorial] | |||

* [http://www.tcl.tk/man/tcl8.5/TkCmd/contents.htm Official Tk Command Reference] | |||

* [https://likegeeks.com/python-gui-examples-tkinter-tutorial/ https://likegeeks.com/python-gui-examples-tkinter-tutorial/] | |||

Latest revision as of 04:56, 11 April 2018

Python is inherently a programming language ideal for data analysis, and it works well by simply entering commands and seeing the results immediately, as we have seen in our short course on Python for Physics and Astronomy.For longer programs, or ones that are used frequently, the code is usually written into a file and then executed from the command line or as an element of a more complex set of scripted operations. However many users prefer a graphical user interface or "GUI" where mouse clicks, drop-down menus, check boxes, images, and plots access with the mouse and sometimes the keyboard. Python has that too, through a selection of tools that can be added to your code.

The most developed core component for this purpose is the Tk/Tcl library. In its most recent versions it provides a very direct way of running your programs within a GUI that is attractive, matches the native machine windows in appearance, and is highly responsive. While this is not the only one, it is a solid starting point and may be all you need. Later in this tutorial we will show you how to use Python running in background behind a graphical interface in a browser window which is another technique that is growing in capability as the browsers themselves gain computing power. However, the Tk library will allow you to build free-standing graphical applications that will run on all platforms on which Python runs.

A Tk Tutorial

An excellent starting point is the Tk documentation tutorial which will take you step by step through how to use this library in Python and in other languages. Work through this one first, and then return here and we will illustrated it with a few examples to show you how to use it in Physics and Astronomy applications.

Building a Program

In the tutorial you will see examples of code segments, and a few complete programs. Here, step by step, is how to make one that you can use as a template for something useful. First, you may see lines such as these at the beginning of a Tk program:

from tkinter import * from tkinter import ttk

which add the needed modules to your Python system. When you use "from xxx import *" that takes all the parts of xxx and adds them with their intrinsic names. Usually this is not an issue for such major parts of Python as tk, but it could cause a problem by overwriting or changing the meaning of something you are already using. Also, even if that is not the case, you cannot immediately tell if a function or constant is from tk, ttk or the core Python. An example would be Tk itself. The next lines of a simple program started this way may be

root = Tk() mainframe = ttk.Frame(root, padding="3 3 12 12")

and if we wanted to use a string inside the tkinter program we would have

mystring = StringVar()

somewhere in the code. The function "StringVar()" is not in the core Python. It comes from tkinter. Without the leading "from tkinter import *" the "StringVar()" is not defined.

For long term maintenance, a better approach is to load the module and give it a short name this way:

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import ttk

or this works too

import tkinter as tk import tkinter.ttk

Now we have to use "tk" along with the component we are taking from tkinter, but the resulting code is much clearer. Let's complete a program that will convert feet to meters, following an example from the Tk website.

def calculate(*args):

try:

value = float(feet.get())

meters.set((0.3048 * value * 10000.0 + 0.5)/10000.0)

except ValueError:

pass

root = tk.Tk()

root.title("Feet to Meters")

mainframe = tk.ttk.Frame(root, padding="3 3 12 12") mainframe.grid(column=0, row=0, sticky=(tk.N, tk.W, tk.E, tk.S)) mainframe.columnconfigure(0, weight=1) mainframe.rowconfigure(0, weight=1)

feet = tk.StringVar() meters = tk.StringVar()

This way, all the tk-specific terms are clear. Notice the constants too, here "tk.W" for example, come from tkinter. Here's the remainder of the program that wil create a calculator window and run the conversion:

feet_entry = tk.ttk.Entry(mainframe, width=7, textvariable=feet)

feet_entry.grid(column=2, row=1, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E))

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, textvariable=meters).grid(column=2, row=2, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E))

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Calculate", command=calculate).grid(column=3, row=3, sticky=tk.W)

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="feet").grid(column=3, row=1, sticky=tk.W)

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="is equivalent to").grid(column=1, row=2, sticky=tk.E)

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="meters").grid(column=3, row=2, sticky=tk.W)

for child in mainframe.winfo_children():

child.grid_configure(padx=5, pady=5)

feet_entry.focus()

root.bind('<Return>', calculate)

root.mainloop()

The result will look like this when it runs:

The elements of the program are

- import tkinter

- define any functions such as "calculate" that you want to run

- create a graphical environment "root" window

- add a frame to the window

- put a grid inside the window frame

- add widgets for your interface located within the grid

- pad the widgets with space so they look good and Tk does the rest

- start the user interface

If you start the Python interpreter in a shell and perform the operations step by step up, as soon as the root object is created, a GUI window will appear on the screen. What comes after determines the properties of that display and its contents. For example, adding a title has a obvious effect to this window.

The window contains a frame which is called "mainframe" here, and when that is added the window shrinks to fit the frame. It is quite small because the frame does not contain anything but a few pixels of padding around its border. You can, at this point grab the edges of the tiny box and stretch it on your screen. The command

mainframe.grid(column=0, row=0, sticky=(tk.N, tk.W, tk.E, tk.S))

creates a grid that is anchored to tk points N, W, E, and S, that is to the corners. Within the grid we add components that will make our interface, and each component has properties we can set too. In this program we will have a frame that will enclose the our interface, and the window will resize automatically to enclose everything. The Tk grid handles the location of the "widgets" that are the elements your interface, and at least for many applications will make creating an nice-looking GUI simple.

First, we add the frame:

mainframe.columnconfigure(0, weight=1) mainframe.rowconfigure(0, weight=1)

Then we define the strings that will hold input and the output from the box that will accept the input:

feet = tk.StringVar() feet_entry = tk.ttk.Entry(mainframe, width=7, textvariable=feet)

The object called "feet_entry" represents this box on the screen. The box is located inside the GUI by the grid that is defined in mainframe

feet_entry.grid(column=2, row=1, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E))

and we put it in column 2 and row 1. As soon as this is issued, a box appears in the GUI and is centered because there is nothing more there. The result of the calculation will be a string that we will show on the interface as a label below the input in the second row

meters = tk.StringVar() tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, textvariable=meters).grid(column=2, row=2, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E))

Notice how the string is given as a variable without quotes, so the interface will update when this variable changes. Along with this, we include fixed labels for the input units, an explanation and the output units:

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="feet").grid(column=3, row=1, sticky=tk.W) tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="is equivalent to").grid(column=1, row=2, sticky=tk.E) tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="meters").grid(column=3, row=2, sticky=tk.W)

Lastly, we add a button that will start the calculation

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Calculate", command=calculate).grid(column=3, row=3, sticky=tk.W)

All of these elements are children of the frame, and to have them appear on the grid with a little padding we take each one and configure the grid for it

for child in mainframe.winfo_children(): child.grid_configure(padx=5, pady=5)

Now focus the window on the entry box to make it easy on the user and use the Return key to start a conversion (as well as the button)

feet_entry.focus()

root.bind('<Return>', calculate)

The GUI is ready to use. Start it with this

root.mainloop()

You will find this program among our examples as the file "feet_to_meters_tk_explicit.example".

Interfacing an Instrument: Phidgets

The power of a graphical user interface or GUI is that it is easy to use when the actions are repetitive and the end user does not need to know the details of what is happening. It will deliver to the user the result that is needed and even provide cues on how to make that happen. As in the calculation of a feet to meters conversion, the GUI does not inform the user of how it is done, and simply does it without a fuss. In a laboratory environment that can be very useful, assuming the user understands the process, and needs the answer on a single click. An example would be if there is an instrument which is capable of making a measurement and the user needs to know the result.

The Canadian Company Phidgets manufactures a wide variety of small modules for the hobbiest, lab, and even industry that provide control of motors, relays digital signal levels, analog to digital (ADC) and digital to analog (DAC) conversion, and environmental sensors for temperature, humidty, pressure, light level, and stress. Their hardware has been traditionally designed to interface with computers using the USB bus, and recently (2017) they introduced a simpler 2-wire interface that is more versatile for some applications. They also make single board computers to run their devices under Linux. Their products are not unlike the famous Rasberry Pi or Beagle Board systems, except they are uniformly supported, consistently manufactured, and offered with supporting opensource software. Conceptually it offers an Internet of Things for the lab. Of course there are many other vendors with similar intent, National Instruments with their proprietary and mostly Windows-only LabVIEW software, Labjack with cost effective versatile interfaces and solid cross-platform Python support, and Measurement Computing with cutting edge interfaces supported in Linux and Python worthy of consideration. Whatever you pick for your lab experiments, if it has a Python library or module, you will have access to the device from within the Python program. Therefore, it may be useful to have an example of what can be done to interface a user with a device through a Tk GUI.

The instrument we will use is an infrared thermometer from Phidgets because it uses interesting basic physics, and it is so easily interfaced the device technology does not intrude on showing the programming elements. The device is very small, and is powered from the USB interface. It consists of an infrared sensing pyrometer that is internally a Peltier array of thermocouples, and the electronics to connect it to the computer through the standard bus. The black anodized aluminum cylinder is baffled such that infrared light from a spot 10 degrees in diameter (1 meter at a distance of 11.4 meters) illuminates the sensor. The electronics make a measurement of the IR radiation by determining the voltage from the Peltier array, which is to say the temperature it reaches in equilibrium with the incident radiation. It also measures the ambient temperature. The signal it gets is fundamentally the blackbody temperature of the 10 degree spot, and the device functions as a non-contact thermometer that can measure from -70 to +380 celsius with a temperature resolution of 0.02 C and an error of 4 C.

The program which uses this device is similar to the one for doing a conversion calculation, but it takes its data from the instrument instead, beginning this way --

#!/usr/bin/python3

# Phidgets IR temperature sensor example program # Driven by IR sensor change # Added utc logging

import sys import time from time import gmtime, strftime # for utc from time import sleep # for delays from Phidget22.Devices.TemperatureSensor import * from Phidget22.PhidgetException import * from Phidget22.Phidget import * from Phidget22.Net import * import tkinter as tk from tkinter import ttk

# # Initial parameters #

global site_longitude global diagnostics global time_utc global temperature_celsius global polling_flag

You'll notice there are modules loaded from the Phidget22 package that the company supplies. These modules have an application programming interface (an "API") that we can use to control are get information from the sensor. The other new items are declarations that some variables are global, meaning that they will be used in other subroutines. The full program is on the examples page tk_temperature.example.

The graphical interface is built as before

# Create the root window

root = tk.Tk()

root.title("IR Temperature Sensor")

# Add a frame to the window

mainframe = tk.ttk.Frame(root, padding="3 3 12 12") mainframe.grid(column=0, row=0, sticky=(tk.N, tk.W, tk.E, tk.S)) mainframe.columnconfigure(0, weight=1) mainframe.rowconfigure(0, weight=1)

# Create Tk strings for displayed information

tk_temperature_celsius = tk.StringVar()

tk_time_utc = tk.StringVar()

tk_temperature_celsius.set('100.')

tk_time_utc.set('0.')

#Add widgets to the grid within the frame

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="IR Sensor").grid(column=2, row=1, sticky=tk.W) tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="Time").grid(column=1, row=2, sticky=tk.W) tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, textvariable=tk_time_utc).grid(column=2, row=2, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E)) tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="hours (UTC)").grid(column=3, row=2, sticky=tk.W)

tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="Temperature").grid(column=1, row=3, sticky=tk.W) tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, textvariable=tk_temperature_celsius).grid(column=2, row=3, sticky=(tk.W, tk.E)) tk.ttk.Label(mainframe, text="Celsius").grid(column=3, row=3, sticky=tk.E)

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Start", command=start_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=4, sticky=tk.W) tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Stop", command=stop_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=5, sticky=tk.W) tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Exit", command=exit_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=6, sticky=tk.W)

# Pad the widgets for appearance

for child in mainframe.winfo_children(): child.grid_configure(padx=5, pady=5)

The sensor is connected to the code as soon as the GUI is built with this

- Open a connection to the sensor and assign a channel

try:

ch = TemperatureSensor()

except RuntimeError as e:

print("Runtime Exception %s" % e.details)

print("Press Enter to Exit...\n")

readin = sys.stdin.read(1)

exit(1)

which attempts to connect to and if that fails exits with an error message. Once connected, it tells the instrument code how to respond to events

ch.setOnAttachHandler(TemperatureSensorAttached) ch.setOnDetachHandler(TemperatureSensorDetached) ch.setOnErrorHandler(ErrorEvent) ch.setOnTemperatureChangeHandler(TemperatureChangeHandler)

which are self-explanatory functions that do something when the event occurs. The important one for our use is

def TemperatureChangeHandler(self, temperature):

global temperature_celsius

global time_utc

global polling_flag

temperature_celsius = temperature

time_utc = utcnow()

if polling_flag:

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f'))

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f'))

Here the global variables are used to communicate with the handler. They take the temperature that is identified as having changed and save it so we can use it in other places, they note the time of the measurement, and they set two tk string variables that will display the temperature and the time. The polling_flag is used as an on/off switch on the user interface. It is changed on response to a button press to start or stop the sensor readings. Alternatively we could poll the sensor ourselves, either by a button press or by a timer of some sort, but this method lets the intrument interface tell us when it has a new value.

# Define the button press actions

def start_irsensor(): global temperature_celsius global time_utc global polling_flag polling_flag = True tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f')) tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f')) return()

def stop_irsensor(): global temperature_celsius global time_utc global polling_flag polling_flag = False tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f')) tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f')) return()

def exit_irsensor():

try:

ch.close()

except PhidgetException as e:

print("Phidget Exception %i: %s" % (e.code, e.details))

if diagnostics:

print("Press Enter to Exit...\n")

readin = sys.stdin.read(1)

exit(1)

print("Closed TemperatureSensor device")

exit(0)

return()

We then start the GUI and let it update the temperature while giving us control to start and stop the updates, or exit the program with a button press.

# # Polling loop within GUI #

if diagnostics:

print("Gathering data ...")

# Temperature change handler will provide new data

# Tk standard is to use this blocking method root.mainloop()

exit()

The running program looks like this:

Events and Control Within the User Interface

When a tkinter program has created the interface the last step is to make it responsive to the user. In these examples you'll see this function call

root.mainloop()

without an argument. That turns over control to the tkinter system that will idle waiting for an event for which it has been told to respond. An example is a button press, as above, which was programmed with a line such as this one

tk.ttk.Button(mainframe, text="Exit", command=exit_irsensor).grid(column=2, row=6, sticky=tk.W)

that created a button to exit the program. When this button is depressed or clicked, the routine "exit_irsensor()" is run. In this example that routine disconnects the program from the sensor and cleanly closes up. Other buttons in our program set flags and variables that determine how the program operates. Notice that the events are all generated within tk. Our external event is a change in the value of the temperature that is measured. That change is sensed by a different process that is running asynchronously and not directly in communication with tk. We have made them work together by having the separate process -- the handler for a change in temperature value -- set the string that displays this temperature. Whenever that string is set, an event is created that tk notices, and it updates the display.

Tkinter programs are designed to use the root.mainloop() function to keep the display responsive to the user. However root.mainloop() is "blocking" any other operations. If, for example, we wanted to poll the device from within our program we could not do that because the program is in an infinite loop looking for user input to the interface. There is, however, a simple solution. Instead of starting root.mainloop() and letting it run, we tell it to also run another routine after it has started. It is done this way:

root.after(2000, measure_temperature) root.mainloop()

The after method takes arguments that are the delay time in milliseconds and the name of the function. The mainloop starts a timer and 2000 milliseconds later it runs measure_temperature()

def measure_temperature():

if polling_flag:

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f'))

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f'))

# Reschedule event in 2 seconds

root.after(2000, measure_temperature)

which upates the temperature on the display if polling_flag is true. It also tells mainloop to schedule another run of measure_temperature after 2000 more milliseconds, and so on.

We have simply modified the previous example where the temperature measurement is done in another process set up by the Phidgets22 library and left the values of temperature and time in global variables for us to use later. More commonly, we could have made the measure here instead by calling that method on the open channel of the device:

def measure_temperature():

global temperature_celsius

global time_utc

global polling_flag

global ch

if polling_flag:

temperature_celsius = ch.getTemperature()

time_utc = utcnow()

tk_temperature_celsius.set(format(temperature_celsius, '3.2f'))

tk_time_utc.set(format(time_utc, '3.7f'))

root.after(2000, measure_temperature)

Here we see for the first time one of the bottlenecks of computing that runs a sequence of commands on a single thread. Because it can only do one thing at a time, it cannot be taking data and displaying it and talking with the operator. To accomplish that you would need multiple threads or multiple processes and a way for these components to communicate with one another and stay in step, that is to synchronize with one another. One solution is to start separate processes that run asynchronously and let them communicate with a protocol you would design. This can be simple message passing through files or first-in-first-out buffers, or something more sophisticated that can manage multiple events with suitable responses. Another is to introduce threading, where the code maintains multiple synchronized paths of processing. Threading can be quite difficult to code however, and it is usually restricted to staying on one processor, so it does not take advantage of the many CPU's that are on modern hardware.

We will encounter this issue again when we look at methods of incorporating responsive graphics and visualization into your programs, since those inevitably will use other modules that will take control of your program and disable the responsiveness of a tk interface. For now, we have solved it by letting the process that takes data alert tk to take another measurement later, effectively building an infinite loop within the tk.mainloop(). This version of the program is on the examples page tk_temperature_polling.example.

Widgets Reference

The Tkinter widgets include the usual ones, and they are simple to implement. For reference, here they are with brief examples. For details that go beyond a tutorial, consult the reference for Tkinter with Python 3, but be aware that as of April 2018 the information in the documentation applied to tk version 8.5 and is not up to date. Similarly, many of the older help lists and examples have to be consulted with caution because they apply methods to "improve" the older tk.

Add Tk

In Python 3 with tk 8.6 and higher use

from tkinter import *

to get the base code, and

from tkinter.ttk import *

to get the ttk library of addition widgets.

When imported in this way, we do not require the "tk." before using its functions. Preferrably, as is good programming practice with other modules and to be clear about what is from tk use

import tkinter as tk import tkinter.ttk

and preface all tkinter commands with tk as we do here. The ttk library must be explicity added and when done in this way its components must be identified with .ttk as well. For example, tk.Label is part of the base, but tk.ttk.ComboBox is added from the ttk library. You have seen examples of this in the tutorial above.

Create a Window

The first thing to do when building a GUI is to create the window it will live in

import tkinter as tk

window = tk.Tk()

window.title("My Application")

window.mainloop()

Not that using "tk.TK()" is required if tkinter is imported as "tk".

Set Window Size

Use the geometry function to set the window size in pixels

window.geometry('640x320')

Optionally Add a Frame

A frame widget inside a window is a container for other widgets. It is optional, and used to simplify layout, add border spacing, or distinguish regions of a window. In the first examples of Tk GUI programming we wrote

root = tk.Tk() mainframe = ttk.Frame(root, padding="3 3 12 12")

and then added widgets to the mainframe rather than to the root. In these examples to make it simpler we add them to the root window without including the surrounding frame, but in a complex user interface you may want to have one or more frames and within them the various widgets to do your work.

Use mainloop()

A tk interface program is made active by invoking the default

window.mainloop()

as above. This enables the tk interface to service events. We have illustrated a workaround when your program needs to do something else by invoking the "after" option, but in general simply running the mainloop is the best approach combined with other processes that are coded to interact with your interface or queried on a button press.

The commands may be entered into an on-line active session and the elements of the interface will appear in real time with each one, the simplest being text inserted into the window.

Create a Label

Labels are added to a window with

lbl = tk.Label(window, text="Hello World")

The label is widget that will appear where it is told to in the window, and is distinct from the title. We use a grid to locate this widget and others in the working window space.

Grid

The grid function locates the widget components within a window, starting from column 0 and row 0 at the upper left. It is a property of the widget and is set with

widget_name.grid(column=x, row=y)

The lbl we created would be added to the window when it is placed on the grid with

lbl.grid(column=1, row=0)

We will not see it until it is assigned to the grid.

There is also a "pack" function which will try to locate the elements in the window for you. The two are not mutually compatible, and grid is the best option to get a nice looking result with minimum effort and maximum control. Widgets may be placed within their grid locations by adding a "sticky" value to their properties as we have seen elsewhere in this section on Tkinter.

Set the Font for a Label

Select the style and size in points this way:

lbl = tk.Label(window, text="Hello World", font=("Arial Bold", 50))

without needing other add-ons to Tkinter. Be cautious in using older methods with Tk version 8.6 and later, which has improved the styling and default selections to make a nice interface out of the box. The fonts that are available will depend on your computer's operating system. One way to tell is to run LibreOffice and see the font names offered there and try those.

Scrolled Text for Output

It may be useful to display more than a few words and confine them to a scrolled box on the grid. For that we need to add

import tkinter as tk

import tkinter.scrolledtext

txt = tk. scrolledtext.ScrolledText(window,width=40,height=10)

txt.grid(column=0,row=0)

txt.insert("insert","Text to display goes here")

The contents can be dynamic, and to remove it from beginning to end use

txt.delete(1.0,2.0)

where the first argument is line 1, character 0, and the second one is line 2 character 0. This deletes all the content within that range. You can delete a specific character by specifying one argument in the format line.character. Similarly, the insert function can be specific to a location, such ast

txt.insert(1.7," My new text has been inserted at character 7 on line 1. ")

Entry for Text Input

An Entry widget accepts user text. You may specify the width of space allocated when it is created:

txt = tk.Entry(window,width=10)

Message Boxes

If you want your program to inform its user about something, then use

import tkinter as tk

import tkinter.messagebox

response = tk.messagebox.showinfo("Title", "Content")

The box pops up in its own window with the title and content you designate (notice it is not connect to an existing window) when it is executed, and it asks for a user to click "OK" to make it disappear. Usually this action will be generated by running code that needs to alert the user to a situation, or by a button press by the user asking for information. In the event of an error or warning, there are two variants that create a different appearance to the user

response = tk.messagebox.showwarning("Title", "Warning Content")

response = tk.messagebox.showerror("Title", "There has been an error")

both requesting an "OK" response from the user. All of these message boxes return a string that is "ok". For other possible responses, tkinter has

response = tk.messagebox.askquestion('Question title','Question content') which returns "yes" or "no"

response = tk.messagebox.askyesno('Yes or no title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False

response = tk.messagebox.askyesnocancel('Yes or nor cancel title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False or no response

response = tk.messagebox.askokcancel('OK or cancel title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False

response = tk.messagebox.askretrycancel('OK or retry title','Question content') which returns boolean True or False

each of which has a distinctive look to the user.

File Selection Menu

To create a file selection dialog

import tkinter as tk import tkinter.filedialog

selected_files = tk.filedialog.askopenfilenames()

and the chosen files are return in a tuple. The entries in the tuple are strings with the full path and file name. The dialog appears in the operating system's default interface, and allows multiple selections with the usual mouse operations.

There are options to select and return a directory

selected_directory = tk.filedialog.askdirectory()

and operating system-specific methods of setting an initial directory

from os import path

selected_file = tk.filedialog.askopenfilename(initialdir= path.dirname("Full path to directory goes here"))

and again the selected file has the full path in its name.

Window Menubar

The window may have a menu added across the top, as most do. To have one with a "File" on the menubar and a "New" in the dropdown that comes from clicking it, use

import tkinter as tk from tkinter import Menu

program_menu = tk.Menu(window) program_menu_item = tk.Menu(program_menu) program_menu_item.add_command(label='New') program_menu.add_cascade(label='File', menu=program_menu_item) window.config(menu=program_menu)

If the window exists, when the configuration change is made the menu bar will appear. Other items may be added in the same way. For example the lines

program_menu_item.add_command(label='New') program_menu_item.add_separator() program_menu_item.add_command(label='Edit')

with a separation between the components. By default there is a tearoff feature at the top that permits the user to detach the menu. It is disabled with

program_menu_item = tk.Menu(program_menu, tearoff=0)

when the dropdown menu is created. Each item in the menu should have a response function added so it really does something when selected

program_menu_item.add_command(label='New', command=new_item_function)

where the "new_item_function" has previously been defined.

Button

Add a button to the interface

btn = tk.Button(window, text="Run") btn.grid(column=2, row=1)

Combobox -- A Dropdown Menu

This widget from the ttk library adds the familar dropdown menu to the interface

my_list = tk.ttk.Combobox(window)

and you would create the selections with

my_list['values']= ("1", "2","More than 2")

The default selection is set with

my_list.current(2)

to pick the item from the tuple used to create the list

Checked Box

A checked selection is made with

tk_chk_state = tk.BooleanVar() tk_chk_state.set(True) chk = tk.ttk.Checkbutton(window, text='This Choice', var=tk_chk_state)

Its value is accessed in code by the setter and getter

tk_chk_state.set(True) or tk_chk_state.set(False) chk_status = tk_check_state.get()

Radio Buttons

A set of "radio" buttons are ones that allow one and only one selection. The would usually be created with text and placed in a grid row or a column like this:

rad1 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='First Choice', value='A', command=radio_selected_1) rad2 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='Second Choice', value='B', command=radio_selected_2) rad3 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='Third Choice', value='C', command=radio_selected_3) rad1.grid(column=1, row=0) rad2.grid(column=1, row=1) rad3.grid(column=1, row=2)

In this example we have added a callback command radio_selected() which would be defined before creating the Radiobutton and would respond according the selection. The callback could be different for each choice. The radio buttons do not have a getter, that is, you cannot ask for rad1.get(). Instead, add a variable to the button

tk_radio_selection = tk.StringVar() rad3 = tk.ttk.Radiobutton(window, text='Third Choice', value='C', variable=tk_radio_selection)

and then get the value of the selection with

tk_radio_selection.get()

Spinbox -- Selecting a Number

Commonly used to set a single number, a spinbox is included in the base Tkinter

spin = tk.Spinbox(window, from_=0, to=100, width=5) spin.grid(column=3, row=10)

The numerical values must be integers. A specfic list of values may be inserted instead

spin = tk.Spinbox(window, values=(16, 32, 64, 128), width=10)

and the list may also be floating point, or text rather than numbers. The default would be set according to the content of this list. If they are all strings, then

tk_spin_input = tk.StringVar()

tk_spin_input.set("Item 3")

spin = tk.Spinbox(window, values=("Item 1", "Item 2", "Item 3", "Item 4"), width=10, textvariable=tk_spin_input)

will cause the default selection to match the textvariable in the configuration of the spinbox. When the textvariable changes, the spin box will also update.

Use Configure to Change Properties

Properties of widgets may be changed responsively withing a program by using the configure function attached to its widget. There was an example above in the handling of an event.

lbl.configure(text="String to use for the label goes here")

and the text may be a string variable, a formatted number, a fixed string built into the code in this example. Similarly, properties of widget such as color may be altered while the program is running.

The attribute "configure" for a widget allows us to change its colors as well, for example

lbl.configure(bg="cyan")

will turn the default background to cyan in real time.

Foreground and Background Colors

Add color to a button background and text with "bg" and "fg", such as

btn = tk.Button(window, text="Run", bg="green", fg="red")

Colors may be precisely set by giving the rgb hex code instead of a name. So for example, to get pure green you would use

bg="#00ff00"

which turns on the green bits and turns off the red and blue bits. Similarly blue would be "#0000ff" and red woud be "#ff0000". There are web tools for trying different mixes and finding a hex code for the color you like. Just type "color picker" in Google search and it should be the top return, interactively displayed in the browser.

Handle Events

If a button is depressed or another event on the interface is detected, you may direct the response to a function:

def my_btn_handler():

lbl.configure(text="Do not touch that button!!")

or any other routine you want. Be aware that the mainloop is blocking, and the interface will be non-responsive while handling the request. It is best to run complex responses as another process and to design communications between processes that may update and set GUI interface features on their own.

Add the callback to the widget when it is built:

btn = tk.Button(window, text="Run", command=btn_handler)

The "command" configuration of the button names the function without the parentheses.

Focus

Focus a program on a particular widget (such as a data entry or drop down menu) with

widget_name.focus()

before starting the main loop, or during execution of the code.

Disable or Enable a Widget

If you want the widget not to respond, disable it by setting the state property

txt = tk.Entry(window, width=10, state='disabled')

or enable a disabled state with the "enabled" property. Widgets are enabled by default.

Adjusting Appearance with Added Spacing

A widget in a window may be padded so that it takes up more space, which with a grid would increase the overall size of the window while making the widgets less crowded. This gives you the option of small adjustments to the appearance of the user interface without sacrificing the convenience of having the code adjust the grid for you. Padding is added by specifying pixels in x and y

lbl = tk.Label(window, text="This lable takes space", padx=20, pady=10) lbl.grid(column=3, row=5)