Experiment with CCD Camera Images

For an astronomer, an image is not necessarily a pretty picture. Indeed the information in each image usually goes far beyond what you can see at first look. Image processing is the technique by which an image can be transformed to reveal (or suppress) selected features, or to extract quantitative information in other forms.

There are three programs we use often in astronomy to acquire, analyze, and modify images:

SAOImage ds9 Aladin ImageJ or AstroImageJ

We may use these in different instances because they offer a different set of features. Aladin, for example is excellent for comparing images with one another and with astronomical data bases, and for making quick color images from several images through different filters. SAOImage ds9 is versatile for acquiring images and interacts in real time with our cameras. ImageJ, written and maintained for biomedical imaging, can be modified for special tasks, and is ideal when we are measuring the brightesses of stars.

In this activity we will use ImageJ because it provides for sensitive control of the colors in an image and preserves all of the information of the original data.

The basics

Astronomical images are most often created by placing an electronic detector such as a Charge Coupled Device camera at the focus of a telescope. CCD cameras have an array of sensors exposed to light focused by the telescope. Each sensor records the light from its share of the image. At the end of an exposure, a computer reads them and measures how much light was received point by point in the image. An element of this record is called a pixel. Just as in the camera of your cell phone, state of the art large telescopes use millions of pixels per CCD detector, and may have arrays of detectors side-by-side to cover large swaths of the sky. We use a camera ourselves in other activities. First, however, we will see how we can view and measure the data they return.

We will work with four images recorded in short exposures with our CDK20 south telescope at Mt. Kent, in Queensland, Australia. We have selected images of the Tarantula Nebula, a region of gas and young hot stars in the nearby Large Magellanic Cloud galaxy. There are four images in the data set, taken on the night of October 4, 2010, at about 15:50 UTC by Dr. Rhodes Hart. Each one is a 30 second exposure -- short by astronomical standards, but just long enough to get the nebula without completely saturating the bright stars. He took 4 images through 4 different filters, each one seeing sky in a different range of wavelengths or colors:

The filters are chosen for making precision measurements of the light from stars, not necessarily ideal for making color images that match what the eye sees. The eye is most sensitive at 550 nm, and only 10% as sensitive at

475 nm in blue, and 650 nm in the red. The CCD camera can sense wavelengths as long as 1100 nm.

Click the links to download the images to your own computer, or if you doing this in the astronomy lab, look for them in the directory called "Image Processing".

- ngc2070_I_ij.fits through the I filter

- ngc2070_R_ij.fits through the R filter

- ngc2070_V_ij.fits through the V filter

- ngc2070_B_ij.fits through the B filter

We have already done some processing on them for you by subtracting the response of the camera to no light (a so-called "dark frame"), and by aligning the images so that when superimposed the stars and other features register.

Using ImageJ

If your own computer will run Java, then you may load ImageJ or run it from the web site. It is already installed on the computers in the astronomy lab. To access ImageJ from your own computer, use this link to our servers:

Select "Download ImageJ for your own computer". We have a version that has additional features for astronomy, but you won't need those for this activity.

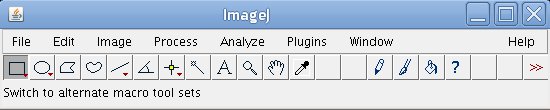

Once you have the software running you'll see a window that looks like this:

Click on File in menu bar to select an image. Other entries offer different options for display and processing. The best way to learn what they can do is to try them out once you have one or more images on the screen.

Loading images

Load the three images taken in visible light in the order R, G, and B:

- File -> Open -> ngc2070_R_ij.fits "R" is red

- File -> Open -> ngc2070_V_ij.fits "V" is the astronomer's visual or green

- File -> Open -> ngc2070_B_ij.fits "B" is blue

It's important to do them in this order because we will make a color image out of them, and the order determines which file becomes which color.

These will appear as 32-bit images, that is values stored in them can be from large negative to large positive numbers.

Run the cursor around and look at the values in the ImageJ control window and you'll see something like this

but it will change as you move the cursor around. The x and y are the coordinates of the pixel, and image is the value representing how much light fell on the image at that spot during the exposure. The numbers may be negative! Oddly that may happen because of how they are stored in the file. Just remember that it's all relative to the lowest possible value, which would be black if no light fell in that spot. For these images black reads -32768.

The first thing you should do, then, is to process the images to change all the numbers in them. Since there are abotu 18,000,000 values in all three images, it's good to know how to make the program do this almost instantly.

Select the "R" image by a mouse click on the top bar of the window.

Process -> Math -> Add -> Value: 32768 -> OK

Repeat for the other two windows.

Making a stack

Notice that we did this operation on each image, one by one. It's simpler to manage several images at once by placing them together in what is called a stack.

Convert all the images to one stack with this simple action

Images -> Stack -> Images to Stack -> OK

Now there is a slider at the bottom of the image display, and if you move it from left to right you select one of the three images. Use the lower slider to select the red image of the stack. Notice that as

you move the slider to the right there are three positions, and the "R", "V",

and "B" image names will appear sequentially in the label of the image window.

Select the leftmost position of the slider to have the red image.

If the new image display range after the math operation makes everything white, then the image may seem to be empty. Just run the cursor around and you'll see that the value changes from place to place.

Use

Image -> Adjust -> Window/Level -> Auto

on the red image. You can experiment with the sliders, but for a start simply let the software do its work with "Auto" which will adjust all three layers of the stack. You wil probably see some stars, but not much detail. The detail is in the low signal levels that are not bright enough on the screen to see.

At this point if you are happy with the result you may save the stack by using

File -> Save as -> Tiff and then enter a name that you will remember, perhaps mystackname.tif

You may load this file and be back at this step instantly should something go wrong later.

Make a color composite

The smallest value in all three images should be around 0, the largest probably less than 32767. A bright star might be 16000 or so, but the nebula that is hidden in this image is only a few 100. If we used a scale of 0 to 255 with the star as 255, then the nebula would be around 255 * 100/16000 = 2. You would not see it. That's what happens on the display you are looking at. It takes a value from 0 to 255 and turns that into a brightness on the screen. At each element you see on the screen there are three numbers from 0 to 255 that tell the display how much red, green, and blue light to show.

Let's make a color composite image so that we can work with this and see the colors.

Image -> Color -> Make composite

The first image will be red, the second green and the third blue. You'll see the color composite of all three on the screen. Each layer has its full range of data, but what you see is limited by the screen's display to a range from to 255 values.